Art as Social Protest

Take a close look at this painting:

It’s a painting depicting a horrific moment in American history: in 1964 three young men who were part of the civil rights movement drove down to Mississippi to look into a church that had been firebombed. The church had been hosting a center to encourage Black citizens to register to vote.

The young men were James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. They never left that town, because they were brutally murdered there.

We’ll get a little more into the history, but first, let’s explore the painting a bit.

It’s obviously harrowing. The first thing we probably notice is Goodman in the center, illuminated with bright light, looking defiantly out of frame. He’s holding Chaney up, and here we see the one real splash of color in the piece: the blood on Chaney’s shirt and hands.

On the right, menacing shadows move toward them, carrying sticks or rifles, we can’t see for sure. Notice, too, how white Goodman’s hands are. Surely the artist is telling us something there.

Now, look in the lower right-hand corner and let’s notice the artist’s name. You will almost certainly recognize it.

Norman Rockwell, one of the most famous American painters of modern times.

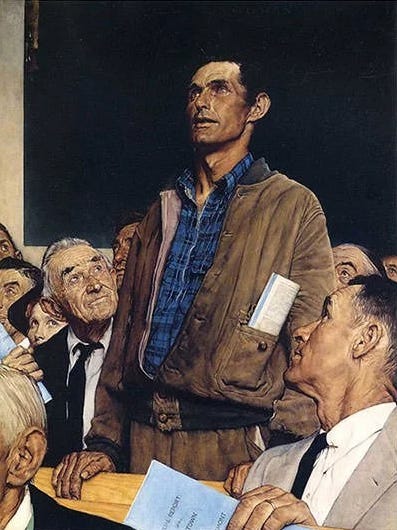

He’s best known for painting like this:

He did paintings about an idealized America, beautiful paintings carefully observed about what it was like to live in the United States. The painting above is one of his “Four Freedoms” paintings, “Freedom from Want.”

His “Freedom of Speech” painting has been heavily memed in the last few years, with people posting it whenever they want to make a big announcement of their own point of view, often in a humorous way:

One thing you’ll note in Rockwell paintings before the 1960s is that they are nearly completely populated with white people. Check out this painting about the freedom of religion, where Rockwell manages to squeeze in a couple people of color:

Now it turns out that this is at least partly because many of Rockwell’s paintings were done for a magazine called the Saturday Evening Post, and the Post had a rule: Black people could only be shown on their covers if they were in a service role.

Regardless, up until the 1960s, Rockwell’s work was, more or less, “white Americana.”

Something changed in the early 1960s. One, Rockwell stopped painting for the Post and started doing work for other magazines, especially one called LOOK, a general interest magazine that did stories about American life that were more expansive than the view at the post.

His first painting for LOOK was about Ruby Bridges, called “The Problem We All Live With.”

Note that there’s only one person whose face we see in this photo. The slur on the wall. The men in lockstep, the splattered tomato. And where is the viewer standing? Well, right in the place where we just may have been the one to throw that tomato. Certainly compared to his earlier work, this painting has something different to say about the American experience. In fact, President Obama hung this painting outside the Oval Office during his presidency.

So let’s go back to the first painting, “Murder in Mississippi,” which was painted for an article called “Southern Justice.”

Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner got pulled over while they were in Mississippi for a “traffic violation.” They were taken to the local jail, where the sheriff called the local head of the Ku Klux Klan and let him know that he had the three boys and was going to let them go shortly.

When the young men were released, the police and several cars full of Klansmen followed. Just before the young activists crossed the county line, the cops barred their way and the men were kidnapped and driven to a remote location where they were brutally murdered. Chaney was tortured and mutilated. Goodman was still alive when they buried them. All three had been shot.

Goodman and Schwerner were both Jewish. Goodman came from a wealthy family, too. So their disappearance didn’t go unnoticed, and eventually — because of pressure from the family and the public — law enforcement looked into things and found the men’s bodies.

Some of those involved were convicted of “violating the civil rights” of the murdered men. Later, a few of them were convicted of manslaughter. No one was convicted of murder despite the use of firearms, slicing up Chaney, and burying them all on a Klan member’s farm.

In Rockwell’s original study he makes it a little clearer who exactly is to blame for what’s about to happen:

Paul Simon, by the way, went to school with Goodman. He later dedicated his song “He Was My Brother” to Goodman’s memory:

I’ve been thinking a lot about art like this. In times of cultural unrest or rising injustice, the artist’s role can be to hold a mirror up to us, to help us see ourselves clearly. It’s chilling to think that the encroaching shadows in “Murder in Mississippi” could be cast by one of Rockwell’s other subjects: the smiling father putting the turkey on the table, the man bravely standing to use his freedom of speech, the cop sitting at a soda counter with a runaway kid. All of those moments were snapshots of American life and culture, but so was “Murder in Mississippi.”

Maybe there was a reason the Post wanted to make sure the Black experience wasn’t examined too closely on their covers.

In any case, it’s fascinating and inspiring to look at the transformation of Rockwell’s work over the years. It’s a reminder to me that artists are called not just to entertain, but to help us see the world and ourselves with clarity.

A poem brought to you by the Mikalatos family

I’m very pleased to say that my daughter, Allie, just published her first professional poem (in other words, she got paid!).

It’s called Untitled (Monkey Mask) and you can read it here! It’s weird but great.

This poem is inspired by Pierre Huyge’s Untitled (Human Mask), which is currently on display at the Met if you want to check it out.

This week on the podcast: learning to love our Christian Nationalist neighbors

This week on the podcast we have Caleb Campbell talking with us about his new book DISARMING LEVIATHAN, a book about learning to love our Christian Nationalist neighbors. It’s a great book and a fascinating conversation, check it out!

Are you on Bluesky?

I am! Let’s hang out. Here’s my profile. I’ve been enjoying Bluesky a lot lately. A whole mess of people have recently joined, so it doesn’t feel quite so empty, and the blocking tools are extremely robust, which means that there’s a lot less performative argument and a whole lot more people talking about things they’re passionate about. I really like it!

KING BRUCE IS KING

BEHOLD HIS STATELY BEARING!

EVEN IN REPOSE HIS ROYAL NATURE PROVES TRUE

UPON THE ROYAL PORCH HE SURVEYS HIS DOMAIN

May you be reminded this week that within King Bruce’s kingdom all are equally regarded, and if one provides royal treats or perhaps head scratches, one shall be high in the royal regard indeed.

Peace to you, as commanded by kingly decree.

— Matt

Partway through the Rockwell portion of this post I realized I had forgotten I was reading a blog post. I was sitting in another art appreciation class there for a minute--and loving it, as usual. The rest of the post was quirky and fun. Love your daughter's poem. Love King Bruce. Thinking about Bluesky. And singing in my head: "Mr. Blue Sky, Mr. Blue Sky, Mr. Blue Skyyy-yyyy..."

My parents loved the folksy themes of Norman Rockwell, and we had several books of his paintings. I often looked at them, and always stopped and studied his 'The Golden Rule'. 'The Problem We All Live With' was included in the books, but not 'Murder in Mississippi'. Knowing Rockwell's other work as well as I do, 'Murder in Mississippi' stands out as a furious howl of righteous anger.